Risk Assessment / Security & Hacktivism

“EPIC” fail—how OPM hackers tapped the mother lode of espionage data

Two separate "penetrations" exposed 14 million people's personal info.

OPM has not yet revealed the full extent of the data exposed by the attack, but initial actions by the agency in response to the breaches indicate information of as many as 3.2 million federal employees (both current federal employees and retirees) was exposed. However, new estimates in light of this week's revelations have soared, estimating as many as 14 million people in and outside government will be affected by the breach—including uniformed military and intelligence personnel. It is, essentially, the biggest potential "doxing" in history. And if true, personal details from nearly everyone who works for the government in some capacity may now be in the hands of a foreign government. This fallout is the culmination of years of issues such as reliance on outdated software and contracting large swaths of security work elsewhere (including China).

The OPM breaches themselves are cause for major concerns, but there are signs that these are not isolated incidents. "We see supporting evidence that these attacks are related to the group that launched the attack on Anthem [the large health insurer breached earlier this year]," said Tom Parker, chief technology officer of the information security company FusionX. "And there was a breach at United Airlines that's potentially correlated as well." When pulled together into an analytical database, the information could essentially become a LinkedIn for spies, providing a foreign intelligence organization with a way to find individuals with the right job titles, the right connections, and traits that might make them more susceptible to recruitment or compromise.

Preliminary evidence points to a group dubbed by Crowdstrike as "Deep Panda," a Chinese cyber-espionage group. In the past, the group has used Windows PowerShell attacks to implant remote access tools (RATs) on Windows desktops and servers. It is this malware that investigators are believed to have discovered on OPM's network and in the Department of the Interior's data center.

Handing out bandages

The two systems breached were the Electronic Official Personnel Folder (eOPF) system, an entity hosted for OPM at the Department of the Interior's shared service data center, and the central database behind "EPIC," the suite of software used by OPM's Federal Investigative Service in order to collect data for government employee and contractor background investigations.Ars contacted both OPM and DHS while researching this story, but officials at both agencies refused to confirm or deny that these systems were part of the breach due to the ongoing investigation. However, sources familiar with OPM projects identified these systems as the ones most likely to be at the heart of the breaches.

In the weeks following the breach discovery, OPM officials scrambled to find a contractor to handle the "Privacy Act event." The organization issued a call in late May and awarded a contract five days later (on June 2) to Winvale Group, a Washington, DC-based technology services company that also helps businesses sell services to the government. OPM classified the transaction as a blanket purchase agreement to allow for multiple additional purchases. The $20.8 million "first call" was for 3.2 million "units" of credit monitoring and identity theft recovery services, indicating the agency's early assessment of how many individuals might have been affected by the breach.

The Winvale Group may get a lot more business based on OPM Director Katherine Archuleta's statement to the House Government Oversight Committee this week. "In early May, the interagency incident response team shared with relevant agencies that the exposure of personnel records had occurred," Archuleta said. "During the course of the ongoing investigation, the interagency incident response team concluded—later in May—that additional systems were likely compromised, also at an earlier date. This separate incident—which also predated deployment of our new security tools and capabilities—remains under investigation by OPM and our interagency partners. In early June, the interagency response team shared with relevant agencies that there was a high degree of confidence that OPM systems related to background investigations of current, former, and prospective Federal government employees, and those for whom a federal background investigation was conducted, may have been compromised."

To date, OPM has no idea how many individuals' background investigations were exposed. All Archuleta said was that the agency was "committed to notifying those individuals whose information may have been compromised as soon as practicable."

In the meantime, the Obama administration has ordered a “30-day Cybersecurity Sprint." Agencies must perform vulnerability testing and patch existing holes in security. They must prune the number of privileged user accounts and expand adoption of multifactor authentication for all systems. The Department of Defense and intelligence community have led the way on that last requirement, but many civilian agencies (such as OPM) have been slow to put it in place.

Just how much this "sprint" will improve government security remains to be seen, especially since agencies such as OPM have been repeatedly warned in the past about minimum "security hygiene." Thirty days is not likely enough time to correct a decade-plus of neglect of antiquated systems, poor leadership, and spotty attempts at modernization.

Employees must wash hands

Enlarge / The OPM Federal Investigative Service secure Web portal, powered by the no-longer-supported Adobe JRun.

By and large, government agencies in the last 20 years have become increasingly dependent on outside contractors to provide the most basic of information technology services—especially smaller agencies like OPM. The result has been a patchwork IT systems and security, and the Office of the CIO at OPM has a direct hand in fewer and fewer projects. Of the 47 major IT systems at OPM, 22 of them are currently run by contractors. OPM's security team has limited visibility into these outside projects, but even the internally operated systems were found to be lacking in terms of basic security measures.

While OPM instituted continuous monitoring of some systems using security information and event management (SIEM) tools, those tools covered only 80 percent of OPM's systems according to a fiscal year 2014 audit by OPM's Internal Office of the Inspector General (OIG) audit team. And as of October 2014, monitoring didn't yet include contractor-operated systems, according to the same organizational oversight.

"The OCIO (Office of Chief Information Officer) achieved the FY 2014 milestones outlined in the roadmap which included quarterly reporting for high impact systems," the OPM OIG reported in its audit. "The next stage in the OCIO’s plan involves requiring continuous monitoring by contractor-operated systems and implementation of the DHS Continuous Diagnostic and Mitigation program." In other words, OPM had no idea what was going on inside contractor-provided networks and only a limited grasp on what was going on within its own network.

There were significant gaps in OPM's security testing as well. Seven major systems out of 25 had inadequate documentation of security testing—four of which were systems directly maintained by the OPM's internal IT department. Three out of the 22 contractor-operated systems had not been tested in the last year; the remainder had only been tested once a year.

The greatest lapse within OPM's security, perhaps, is the way that it has handled user authentication. The OPM IG report has found progress on access controls, including the use of multi-factor authentication to access OPM's virtual private networks and even to log into workstations using Personal Identity Verification (PIV) card readers—essentially guarding the entry points into the OPM network. But "none of the agency's 47 major applications require PIV authentication," the Office of the Inspector General reported, a violation of an Office of Management and Budget mandate for federal systems.

OPM's Office of the CIO responded that "in [fiscal year] 15 we will continue to implement PIV authentication for major systems."

Ironically, federal officials have been blaming the messenger to some degree through anonymous statements to the press. NPR reported that investigators were looking into whether the IG report "tipped off hackers to some of the agency's vulnerabilities," and reporter Dina Temple-Raston found that investigators believed the attack came "about a month" after the IG report was published. "Among the things the inspector general found that could have helped hackers was that nearly a quarter of the agency's systems did not have valid authorization procedures," she said. "The reason that's important is because one of the departments that didn't have the correct procedures was the Federal Investigative Services. That's the group responsible for background investigations of federal employees. So that data's very sensitive, and as we know now, this is one of the databases that was hacked."

But those problems had been well-documented prior to the 2014 IG report. Attacks on two OPM investigative contractors—USIS and KeyPoint—could have provided plenty of intelligence on just how bad OPM's systems were. Even a quick Web search would have given attackers plenty of ideas about how to get into OPM's sensitive systems. For example, the "secure" Web gateway to OPM's background investigation systems is a contractor-hosted website at an application service provider. That Web gateway is reached through a Windows Web server running JRun 4.0, Adobe's Java application server, as well as ColdFusion, a platform that has been used for a number of breached government servers in the past few years.

In 2013, someone hacked into Adobe and stole the ColdFusion source code. And Adobe dropped the JRun product line entirely in 2013—with extended "core" support ending in December of 2014. There is no evidence that OPM or its application provider had purchased expensive extended, dedicated support, but JRun would hardly be the only unsupported platform still used by OPM. The agency still has systems based on Windows XP (supported under a custom support agreement with Microsoft), and many of the core systems run by the agency are based on mainframe applications that haven't been updated since their COBOL code was fixed for the Y2K bug in the late 1990s.

It would be incorrect to say that these older systems (especially the COBOL code) couldn't be updated to support encryption, however. There are numerous software libraries that can be used to integrate encryption schemes into older applications, including libraries from PKWare. Other government agencies and financial institutions already utilize such software, according to Matt Little, VP of Product Development at PKWare. The problem is that, as DHS Assistant Secretary for Cybersecurity Andy Ozment noted during his testimony, OPM didn't have the kind of authentication infrastructure in place for its major applications to take advantage of encryption in the first place. Encryption, he said, would "not have helped in this case."

Since multi-factor authentication and encryption were not integrated into any of OPM's 47 major applications, all an attacker had to do was to gain access to a system on the network—nearly any system. Based on the testimony before Congress and other publicly available data, we know that hackers found at least two systems and were able to easily expand their access laterally within OPM and then contractor and service provider networks afterward.

"There's a process failure in every spot there," said PKWare's Little. "It's just bad security controls. It looks ridiculous—they didn't even have basic IP (network) access controls. This is not something we typically see in a serious security customer."

As Ars has reported, those problems were not just found at OPM itself. Contractors working for the agency may have introduced some unique security issues of their own, including employing Chinese nationals—some working from overseas—as part of subcontracting teams. Allegedly, that project was an implementation of SAP's SuccessFactors software, undertaken by a systems integrator for OPM and affiliated agencies, and included access to employee personnel data for the Department of Energy, the Transportation Security Agency, and others. SuccessFactors is used as part of a human resources system called the Talent Management System (TMS), "an integrated learning management and performance management system based on the industry leading SAP/Plateau/Success Factors software" hosted for multiple agencies by a data center at the Department of the Interior. SAP could not provide information about the program, the integrator, or even confirm that Interior or OPM were a customer without OPM authorization.

The wrong kind of file sharing

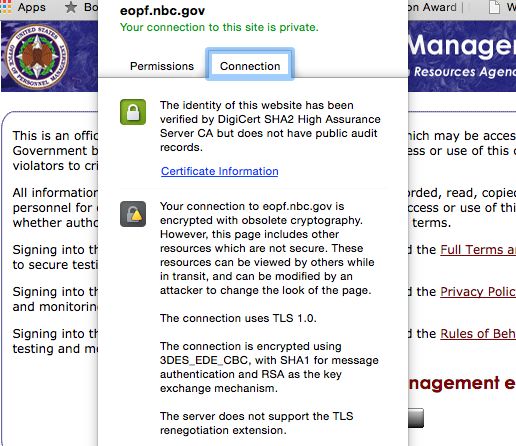

The login page for the Web gateway to the Electronic Official Personnel File (eOPM) hosted at the Interior Business Center may have had some security weaknesses, as shown by Chrome.

Initially, the investigation into the OPM breach uncovered an infiltration into personnel file databases, which may have included the Central Personnel Data File. That database includes the personnel records of a majority of federal employees. The data breach, based on testimony provided by federal officials, included an intrusion into an OPM system hosted by an outside service provider: the Department of the Interior.

The Interior Business Center, formerly known as the Department of Interior National Business Center, is what's known as a shared services center. That means it gets its funding by bidding for work from other government agencies, occasionally competing against outside contractors. So the IBC has been a relatively active center of innovation in the US government as a result. The center has been in the government cloud business since before the Obama administration, providing infrastructure and software as a service. The IBC uses its IBM mainframes, database instances, and mainframe Linux instances (along with other servers) to do everything from serving up webpages to running payroll for dozens of agencies. IBM even profiled IBC (then NBC) for a case study on using System z mainframes as an enterprise cloud platform.

Starting in 2011, OPM pushed agencies to adopt approved Human Resources Line of Business (HR LOB) applications running at federal and commercial shared service centers, hoping to save a billion or more over four years by using more generic federal human resources applications hosted at both federal and commercial shared services centers. But even before the Obama administration had begun its big push to consolidate federal data centers under Chief Information Officer Vivek Kundra, NBC was providing IT services for more than 150 government agencies (often as Web-based software-as-a-service offerings).

IBC also offered mainframe capacity through "infrastructure-as-a-service" packages to other agencies. And as OPM was seeking to consolidate its own data center operations, it turned to IBC to host the eOPF system—the electronic version of government employees' personnel files. The eOPF system's data includes the electronic version of the SF-50 (Notification of Personnel Action), which a State Department human resources document referred to as "Your Federal Employment Birth Certificate." It documents a federal employee's career—promotions, demotions, other administrative actions, retirement plan, and work schedule, as well as personal identifying data. OPM maintains eOPF records for millions of current and former government employees, including Congressional staffers.

At some agencies, eOPF is only accessible from within departmental networks. But some agencies, including OPM, have Internet-accessible portals into the eOPF system. Apparently, eOPF's servers are accessible over the same Internet gateway that other agency Web servers running in IBC used. It's also behind the same firewall. So exploiting one of the Web servers operated by IBC would have given attackers access from within the firewall to eOPF and, in turn, to the OPM databases and services connected to it.

That much was confirmed by Interior's CIO Sylvia Burns, who said in her statement to the House Government Oversight Committee that there was evidence "the adversary had access to the DOI data center’s overall environment." As a result, DOI is "accelerating" a number of fixes. "As part of DHS’s Binding Operational Directive (BOD) we are identifying and mitigating critical Information Technology (IT) security vulnerabilities for all Internet facing systems... We are fully enabling two factor authentication for privileged users (e.g., system administrators, etc.), as well as regular end-users."

In other words, once the attackers had gained access to login credentials of a "privileged user" in IBC's data center, they had the keys to the kingdom. Burns also said that improvements were being made to the way networks within the IBC data center were isolated from each other, an attempt to prevent attackers from exploiting systems connected to the Internet in order to access the rest of its infrastructure.

And the eOPM Web interface itself may have been susceptible to breach. A check of the site's Internet-facing login by Ars found "obsolete" crypto—the site still uses TLS 1.0. There were also insecure elements on the page which might have been modified by a man-in-the-middle attack to fool users into giving up credentials.

In a notice to federal employees about the breach, OPM obliquely confirmed that eOPF had been breached:

The kind of data that may have been compromised in this incident could include name, Social Security Number, date and place of birth, and current and former addresses. It is the type of information you would typically find in a personnel file, such as job assignments, training records, and benefit selection decisions, but not the names of family members or beneficiaries and not information contained in actual policies.While the attackers had full access to IBC's data center, it so far appears that they didn't pull data from the HR LOB applications run there. Data available there would have been more interesting to thieves interested in financial gain, but the eOPF data is more interesting from an intelligence perspective because it profiles government employees. Such information might indicate things like whether they had problems in the workplace and might be susceptible to recruiting efforts.

Even so, eOPF isn't nearly as dangerous to both federal employees and the government at large as the other system at OPM that got hacked: EPIC.

Tell us a little about yourself

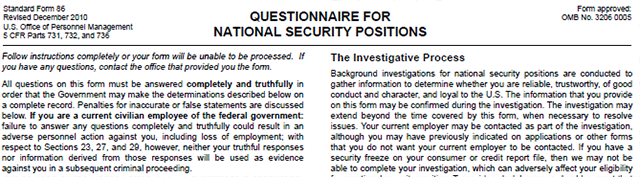

The header to SF-86, the questionnaire filled out by all candidates for security clearance background investigations. All that data goes into OPM's CVS.

- E, for the Electronic Questionnaires for Investigations Processing (e-QIP) system, a "Web-based automated system...designed to facilitate the processing of standard investigative forms used when conducting background investigations for Federal security, suitability, fitness and credentialing purposes." The e-QIP system provides a "secure Internet connection"—a Web-based HTTPS portal, based on Adobe ColdFusion—to "electronically enter, update and transmit their personal investigative data over a secure Internet connection to a requesting agency."

- P, for the Personnel Investigations Processing System (PIPS), a background investigation case management system that handles individual investigation requests from agencies. In addition to handling the scheduling and processing of background investigations, PIPS contains the Security/Suitability Investigations Index (SII), a master record of background investigations conducted on government employees. This is consulted whenever a "National Agency Check" is run against a person as part of a background investigation.

- I, for Imaging—as in the PIPS Imaging System—a viewer for digitized paper case files. Paper surveys, questionnaires, written reports, and other images are stored here in a system based on IBM's Deaja ViewOne.

- C, for the Central Verification System (CVS), the mother lode of background investigation data. According to OPM, it contains "information on security clearances, investigations, suitability, fitness determinations, Homeland Security Presidential Directive 12 (HSPD-12) decisions the background checks required for employees and government contractors to gain access to federal facilities, Personal Identification Verification (PIV) credentials [the government ID cards used for facility access and as a second factor in authentication systems], and polygraph data." In 2014, OPM increased the scope of CVS to accept security clearances granted to state, local, tribal and certain corporate employees to meet the needs of the Department of Homeland Security. CVS is also "bridged" to the military's Joint Personnel Adjudication System (JPAS), the Department of Defense's own clearance system for uniformed and civilian employees, so that contractors performing background checks can reach into DOD data when performing background investigations.

In a fiscal year 2014 annual report, officials at OPM's Federal Investigative Service wrote, "At OPM, the security of our network and the data entrusted to us remains our top priority. OPM FIS took steps to strengthen security protocols imposed on its own information technology systems and those of its contractors in an effort to preempt any malicious incident that could cause harm to the privacy of individuals or our national interests."

Despite those steps, two OPM investigative contractors—USIS and KeyPoint Solutions—discovered data breaches in 2014. And while some of the elements of EPIC may have been protected from external attack by being located in federally owned secure data centers, it was the breach of OPM's own departmental network that led to the exposure of the contents of the CVS system. While users of OPM FIS' "secure Web portal" are prompted for two-factor authentication (or at least, that's what the code on the site's ColdFusion-powered login page suggests), only a single set of credentials was required from inside OPM's network to gain access to data.

The malware behind the attack, which could have resided on a FIS workstation or nearly any other system within OPM, could then use those credentials to issue queries against CVS and sneak the data back out of the network over the Internet, hiding its activity internally among normal CVS traffic. It was only when OPM was assessing systems to actually implement the sort of continuous monitoring tools that the Federal Information Systems Management Act dictates that OPM security officers discovered traffic outbound from the network that indicated something was very, very wrong.

The damage done to national security by this breach far exceeds anything that could be claimed in relationship to the documents leaked by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. In total, more than 10 million people have active background investigation files in the CVS—either because they have been investigated for a security clearance, or just to obtain permission to work inside federal facilities. Those include all the data from the SF-85 and SF-86 personal survey forms they have filled out detailing much of their personal lives. They include police, fire, and other emergency personnel at state and local levels who have contact with federal anti-terror "fusion" centers, DOD investigators and intelligence analysts. The only agency that may not have been affected is the CIA, which maintains its own background investigation and clearance system.

A lack of imagination

The weaknesses that were exploited at OPM were ones that weren't just discovered overnight—they were problems that had existed in some form for over eight years and possibly longer, exacerbated by outsourcing and poor leadership and planning. These problems are all too common among government agencies because of the "checkbox" approach that agencies have taken to information security.With the "checkbox," agencies measure their security based on whether they have done something that matches against a particular FISMA regulation or used a technology that meets the National Institute of Standards and Technology's (NIST's) Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS), allowing agencies to achieve security "compliance" without really being secure, according to security experts who spoke with Ars. And while the Defense Department and intelligence agencies have taken a more aggressive stance on security measures, few agencies have ever taken the decades-old approach to security that the military pioneered for classified systems: having someone "red-team" them with penetration tests that resemble actual attacks.

"One of the things they struggle with is a failure of imagination," said FusionX's Parker. "The 9/11 attacks happened because we had a failure of imagination in terms of what hijacking was. It's the same with cyber. People aren't gaming things enough—not doing it in tabletop exercises, but doing it for real." While the government holds security exercises like "Cyber Storm", DHS' biennial effort, these are still essentially the paper-based roleplaying game version of security.

While the White House pushed forward with executive orders calling for penetration testing as part of the "30 Day Sprint" launched by President Obama last week, Parker said that he's still "seeing decades of box checking and a lack of realistic threat simulation." These sorts of tests are useless if the goal is understanding how attackers might exploit systems in unexpected ways, he said. "Like Mike Tyson said, 'Everyone has a plan, and then they get punched in the face.' Where these adversaries are catching people with their pants down is the unknown unknowns."

Bringing an approach from military training, where "train like you fight" has long been a mantra, would certainly help. But that's unlikely to happen without major changes to government security policy and culture. "Everything is focused on box checking," Parker noted. He added that his company doesn't do work in the federal market "because there's still a lowest bidder mentality there. If you're a CISO in a private company and you get hacked, and you get called into the boardroom and they ask you what is your procurement philosophy, and you say you went with the lowest bidder, you're going to get hung out to dry."

Instead of addressing some of the underlying problems, government agencies' approach has largely been to throw more people at the problem—Information Systems Security Officers (ISSOs). As of last October, OPM had hired seven ISSOs to take over management of systems security and had another four in the hiring pipeline. Parker said this is akin to "putting as many people around a bad fort instead of rebuilding a better fort." And while great heaps of money are being spent on cybersecurity systems, agencies could likely get a better result spending that money on "fixing systems that are 10 to 20 years old that have never been upgraded."

But these efforts won't happen without a sea change in culture, procurement approaches, and Congressional funding. Until then, expect to hear about more breaches—likely at an increasing rate.

No comments:

Post a Comment